The Three Eras of Game Publishing and Why Advocacy Often Wins

With 50 games being released on Steam every day, it’s becoming increasingly harder for new games to stand out. What should publishers be prioritizing? What’s still effective today?

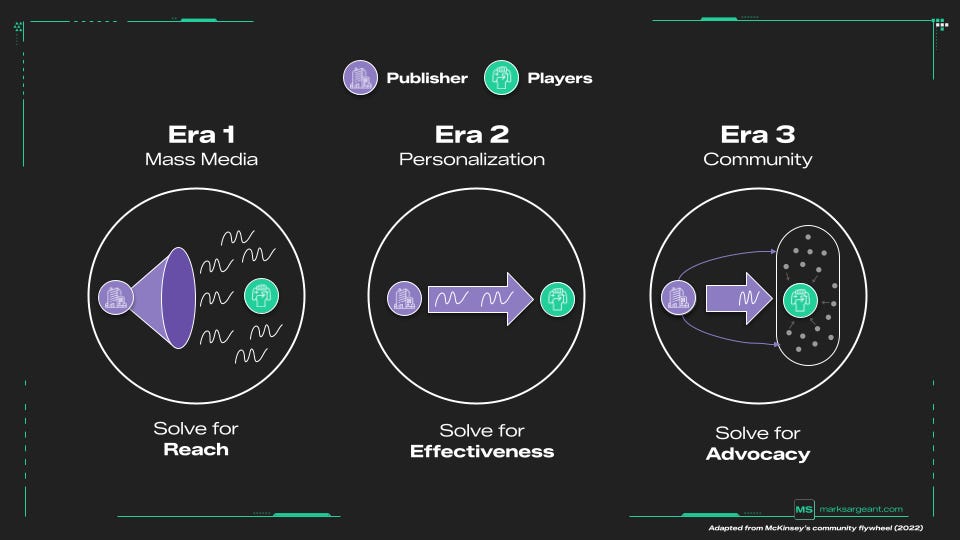

To answer this, my argument centers around the idea that we’ve been progressing through different eras of game publishing. With each era change, new rules, methods, strategies rear their head. Game publishers that have progressed through the eras and can masterfully apply the lessons of each of them, tend to emerge victorious.

Era 1: Mass Media

Before the digitization of games publishing, the most important thing for games to do was to solve for reach. The goal was to be everywhere: linear advertising, billboards, retail shelves, game stores, and so forth. The loudest game usually won.

Large publishers at the time, think of companies like Electronic Arts for example, commanded significant control of a game’s ability to reach its audience. Without them, games couldn’t really reach their audience efficiently. In many ways, having the available capital and relationships to increase reach was paramount. Media scale was the moat.

Communication with players tended to be more of a monologue. Information would flow outward, but feedback flowed back slowly, if at all. There were only very limited, direct player channels. And though communities existed, they were rarely mobilized or thought about in the way we do now.

At the heart of this was the fact that there was an acute scarcity of supply in games. We just didn’t make as many then, as we do now. Discovery was constrained by shelf space, media slots, and calendar moments. Players weren’t being accosted with games left, right, and center. This meant attention would cluster naturally. In a way, the limited shelf space, fixed TV and magazine spots forced almost a sense of brutal prioritization. You were either visible or you weren’t. Distribution itself filtered the market. Marketing amplified that filter.

While conversion likely wasn’t tracked in this way it is today, let’s say that in most cases you’d get a 1-4% conversion. Then the idea was just to drive as much volume and reach as you could, and you’d eventually be successful. Conversion was really difficult to control since there wasn’t really a way to personalize your unique value proposition. Tailoring your creative and messaging was cost prohibitive and often not even possible, not until the digitization of games, which really started to kick off in Era 2.

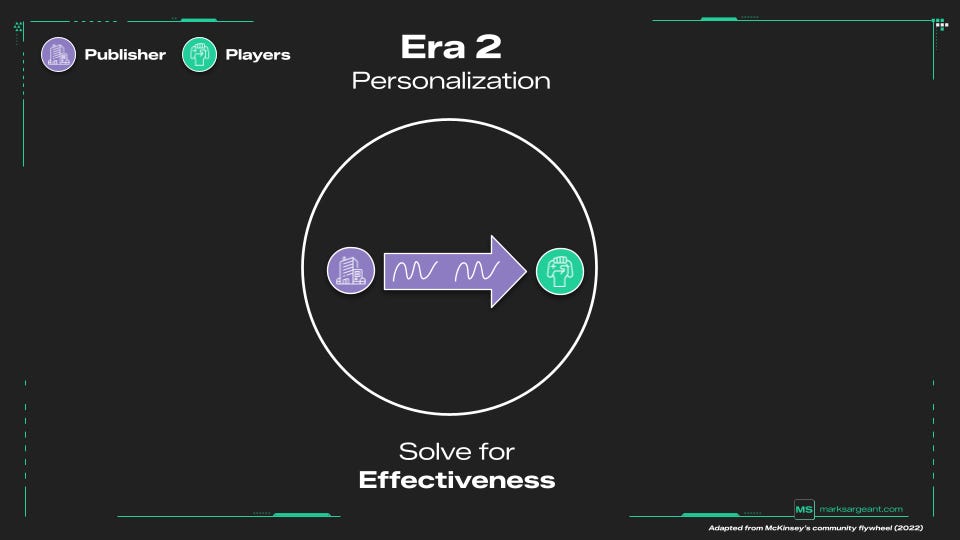

Era 2: Personalization

With the advent of digital distribution, players could now access games immediately through digital platforms like Steam, and eventually the app stores of mobile phones. This ushered in a new wave of games, with the supply of titles rapidly rising from a few hundred titles in the early 2000s to tens of thousands today. Digital distribution turned game supply from a trickle into a flood. That rapid growth in available titles reshaped how players discovered and engaged with games, and shifted the bottleneck to trying to find the right player for your game.

Steam, PlayStation, and other digital distribution platforms began aggregating large player audiences and using engagement, purchase, and social signals to recommend games they believed players would like. Discovery increasingly shifted from editorial judgment and broad marketing beats to algorithmic recommendation. In this era, publishers started to become more specific about who they were trying to reach, and tried their best to control the perception and message those players would receive about a prospective game.

The platforms themselves diverged in how they monetized that influence. Some, like Sony, offered differentiated or premium placements that could be directly paid for. Others, most notably Steam, limited the ability to buy reach or effectiveness outright, instead rewarding engagement signals and player behavior, and of course, inherently good games. This lowered the barrier for independent developers to reach audiences directly, who could now do so without a traditional publisher acting as a gatekeeper.

Publishing technologies also started to improve dramatically. Programmatic advertising, lookalike audience targeting, automated bidding, lifecycle marketing, and other similar approaches finally allowed publishing to tailor specific messages for many different player segments at scale. Or as we saw eventually, let the algorithms operate that independently, with the publisher’s role somewhat reduced to feeding the system an inordinate amount of creative assets and copy so an endless set of permutations could be tested, in the hope of finding the perfect message or creative for a player’s circumstance.

Many of the early mobile pioneers, like Supercell, Playrix, King and a handful of others, benefited from arriving early to a structurally favorable, nascent market. Distribution was frictionless, competition was limited, and the app stores themselves were still learning how to surface games. These publishers built close working relationships with Apple and Google, spent an inordinate amount on “user acquisition”, and were able to capture significant market share of mid-core and casual audiences before the paid programmatic market became saturated.

Just as importantly, they mastered lifetime value economics. By rigorously managing how much they were willing to pay to acquire a player relative to what that player would generate in revenue over time, growth became something that could be modeled, and to a degree, engineered. Marketing shifted from reach and volume, to personalization and optimization - pulling spend up or down based on measurable return. For a period, this created the illusion that growth was a solvable equation, not a fragile balance dependent on timing, market conditions, product differentiation, and crucially, a deep understanding of the player.

At its peak, this approach worked extraordinarily well. Personalization, optimization, and disciplined spend allowed publishers to scale with confidence. Growth felt measurable and controllable. If the numbers penciled out, success wouldn’t be too far behind.

But this era also trained the industry to overestimate its own agency. As competition intensified and supply continued to flood the market, the same levers produced diminishing returns. Acquisition costs rose sharply, and unless a game was prepared to monetize extremely deeply - and be backed by significant capital to reach scale (as seen with titles like Monopoly Go from Scopely) - success became increasingly elusive. At the same time, players grew more skeptical of advertising and became harder to persuade through manufactured messaging alone.

Crucially, players stopped behaving like endpoints in a funnel. As gaming became more mainstream, players became stronger, active participants in networks: talking to each other, forming opinions, and shaping perception well outside the reach of any single campaign or algorithm. Players have always shared their passion for games, but nowhere at the same level of scale as we see today, where games are often the primary 3rd space for young people. Discovery ceased to be something publishers could just engineer directly and instead emerged from player-to-player dynamics they could only influence indirectly. This shift marked the transition into what I describe as the third era of publishing.

Era 3: Community

In Era 3, community isn’t just something that forms after a game is successful. My belief is it’s actually one of the things that produces game success in the first place. In this mental model, growth doesn’t flow predictably from awareness to conversion. It compounds through a flywheel where engaged players become advocates, advocates drive discovery, and discovery brings in more engaged players. The central challenge in this era is not reach or efficiency, but solving for advocacy.

Players, not the platforms or publishers, create the majority of reach, and in many cases determine a game’s ability to convert at all. Streams, clips, Discords, social feeds, group chats, and friends do more to drive discovery than ads, store placements, or media spots. This isn’t “word of mouth” in the old sense, but rather word of mouth at internet scale. And largely outside a publisher’s direct control.

One useful way to frame this shift is through the lens of “belonging”. Players are more likely to advocate for games that feel like theirs - games that reflect their own values, taste, or identity, and connect them to others who feel the same way. When they are satisfied with the game, but also have that sense of tribal belonging, that’s when you’re able to create advocates. Satisfaction and gameplay resonance definitely matters, but it isn’t enough. Advocacy emerges when enjoyment is paired with identity. These are the players who explain the game, defend it relentlessly, and recruit others without being asked.

This reality fundamentally changes the publisher’s role. Control effectively gives way to influence. Communities interpret and shape a game’s meaning in ways no campaign can fully predict or manage. Publishers can’t dictate the narrative, but they can shape the conditions under which it forms. Who you invite in early, what behaviors you reward, the norms you reinforce, and the kinds of moments the game reliably creates all now matter enormously. This is especially true if you’re making a live service game, where you’re very much shaping the product with players.

As a result, my belief is that product, community, and marketing all collapse into a single system. Publishing isn’t just something you layer on at launch. It has to be embedded in game systems that generate stories, tools that enable ease of expression, and live moments that players react to together. If the game doesn’t naturally create conversation, and reach a sense of cultural salience, no amount of after the fact community “management” can force it to spread.

Era 3 also raises the cost of ambiguity. Broad appeal often produces weak advocates. By contrast, a sharp audience definition (being explicit about who the game is for and why) is far more likely to produce avid advocates. That means getting specific: the player’s age and life stage, the games they already play, their broader cultural context, where they congregate, the deeper motivations driving their play, and understanding the relationship they have with you or your IPs. Most importantly, it means understanding why they would stop playing their current game, or scrolling TikTok, to make room for your game.

What comes next

Don’t be fooled though. The mistake would be to think these eras just outright replace one another.

The reality is that all three eras are still very much in play today. Successful publishing blends all three. Reach still matters. You still need moments that go wide and create baseline awareness. Personalization and optimization still matter. Funnels still exist, and economics still have to work. But neither is sufficient on its own. Advocacy and community, in my opinion, should be the dominant ingredient.

The strongest publishers don’t reject earlier-era tools; they use them in service of something larger. Broad beats create entry points. Riot’s season start cinematics still pop off each year. Targeting players more specifically is still a great way to reduce friction. But sustained growth, that doesn’t break the bank, comes from players who care enough to speak on your behalf. To get there, the publisher’s role needs to move upstream -- deeply embedded with product strategy. Such that you can design the systems that allow advocacy to flourish.

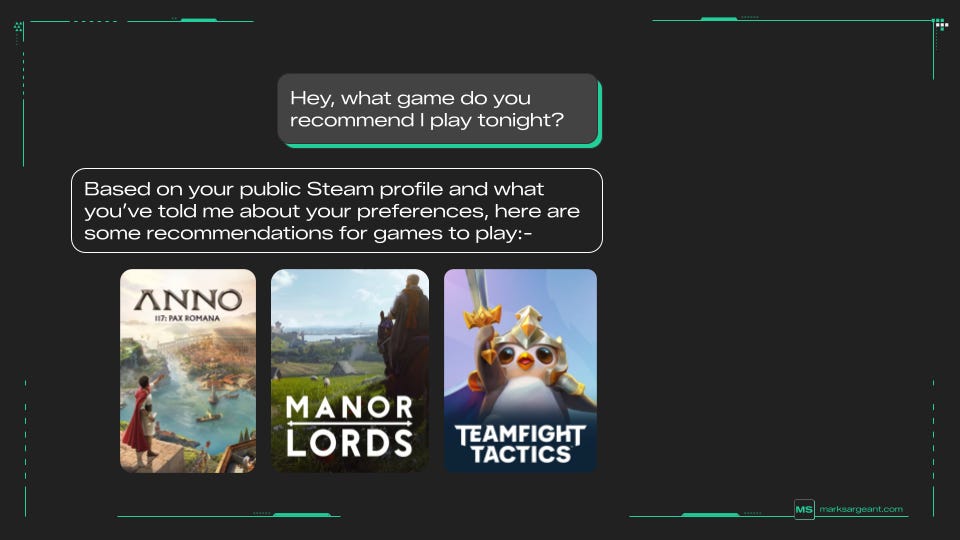

One could argue we may be approaching the edge of Era 4. As young players - particularly those many new games are trying to win - show increasing signs of loneliness and isolation, some are turning to AI as a substitute for human connection and belonging. Early research suggests a meaningful portion already uses AI for social interaction and companionship. As more cognitive and social offloading occurs, it’s worth asking whether discovery itself could shift again. With some of the human nodes in a player’s network being replaced by AI intermediaries? A world where an assistant or companion understands your gaming tastes better than anyone else, and where developers try to manipulate the levers by which AI understands and recommends your game to players. That’s a topic for another piece though.

For now, the takeaway is simpler: advocacy has become the hardest, most valuable and least substitutable part of publishing. But the best publishers can blend approaches from all three eras.

In future essays, I plan to go deeper on advocacy itself - the specific concepts game teams should try to understand and prioritize against.

If this resonated, or annoyed you in a useful way, I’ll be writing more about defining your audience, positioning your game, solving for advocacy, AI trends for publishers, and games distribution more broadly.

Mark, this is the cleanest articulation of the shift I've been tracking with studios building for 2027.

Era 3 isn't just "community matters." It's that advocacy has to be designed into the product from pre-production. The studios I work with who understand this are building Discord communities 18 months before launch, shipping Early Access as community infrastructure, treating mod tools as product features not marketing add-ons.

"Community isn't just something that forms after a game is successful, it's actually one of the things that produces game success in the first place" that's the diagnostic question we're all dealing with in the industry wiht the calendar chaos we've dealt with as of late. If you had to delay launch by six months, what happens? Era 2 thinking: momentum dies, marketing spend wasted. Era 3 thinking: community keeps building, launch becomes an event in the community not the reason for it.

Gen Alpha's already operating in Era 3 by default. They collaborate to grind, mock FOMO tactics, route around extraction mechanics. They're not responding to personalized targeting. They're responding to tribal belonging and peer verification. The games winning them over are the ones where advocacy is baked into the loop.

Curious about your Era 4 thesis on AI intermediaries. Gen Alpha grew up in algorithmic feeds. They already understand how to game recommendation systems. If AI becomes the discovery layer, they'll figure out how to route around that too.