The Power of One: Why Your Game Needs a Muse

How focusing on a single, ideal player accelerates decision making and solves the “beige” game problem.

Most of the time, my observation has been, when developers start building a new game, they start with a mirror. They look at their own Steam libraries, their own late night gaming sessions, and their own frustrations with the games they’ve grown up with. They become the “target player”.

Honestly, it’s a solid way to work. You know your own brain. You don’t need a focus group to tell you if a mechanic or design feels like a chore because you’re the one playing and feeling that pain at 2AM. If there are a million people just like you, and they actually have the headspace to switch to your game, it might be best to follow that path. Plus, when you’re building and playtesting the game, you’ll be sure to have a blast.

But here’s the challenge: what happens when you shouldn’t be developing for yourself? Maybe you’re building in a genre you used to enjoy but has since faded out of the zeitgeist (e.g. RTS games), or perhaps the “you” of 10 years ago isn’t the person buying and investing time in games today. Or you’re just a League of Legends diehard, but you’re on a dev team making a cozy farm sim. That’s when I believe the mirror breaks, and it’s no longer clear who you’re building a game for. And you try to figure out who to serve.

The trouble with player segments

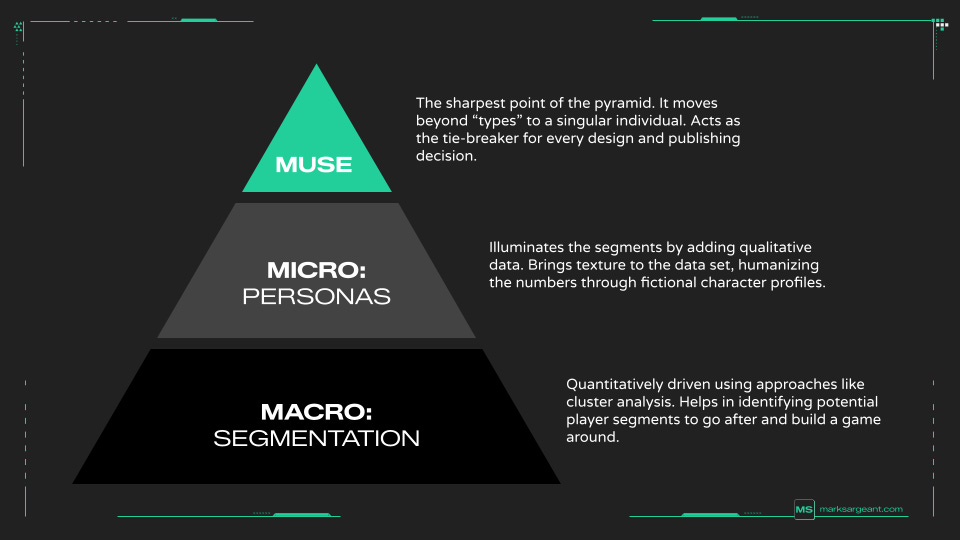

If you’re starting from a blank page, you might try something like a cluster analysis. Where you start quantitatively grouping players by common factors. Or more often you start reverse engineering your audience from players who actually resonated with your game in early playtests or concept tests. The end result is a set of segments, or personas. Things like “Competitive Achievers” or “Social Explorers”. These are certainly helpful, and they definitely give you a picture of different potential motivations and types of players you could serve. They are great for understanding the landscape, but they’re often a bit too cold and generalized. And often encapsulate a population far too large to be considered a “bullseye” player.

You end up trying to please everyone in a 20% slice of the market, and the result is often a game that feels a little…beige. If you try to build your game for a “segment”, you risk making something that no one actually loves, even if a lot of people like it. You get NPS scores in the 7s and 8s, but very few 9s and 10s. My opinion is that a 7 is a death sentence in a crowded market. It means they didn’t hate it, but they won’t tell their friends about it. So what gets you to those 9s and 10s?

I’m a strong believer in going sharper. You need a muse.

What is a muse?

The muse isn’t a group or a segment. It’s a specific, single, individual.

Think of them as the ideal advocate for your title. If this person loves your game, they’ll become your strongest supporter. They usually sit inside one of your segments, but they have a set of unique behaviors or characteristics that stand out. You should be able to define them clearly:-

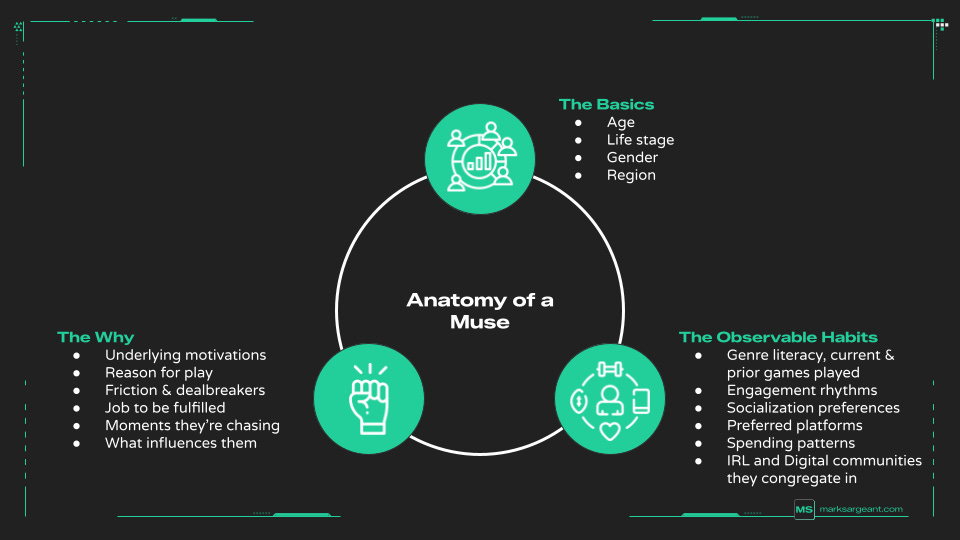

The basics: Age, life stage, gender, and where they live

Observable habits: What gaming platforms do they prioritize? What time do they play? For how long? Who do they play with? What are they playing right now (and why are they slightly bored of it?), and what are their typical spending habits? Where do they hang out IRL and online?

The “why”: These are the psychographics and underlying motivations. You won’t be able to observe these, but you need to develop an initial hypothesis. What actually drives them to play? What frustrates them? What job does your game fulfill? What makes an experience feel meaningful and worth it?

Some examples

Let’s look at a few outside examples. I’m speculating here, but it’s likely helpful to see how this focus manifests in the wild. Note, it’s entirely possible these games didn’t have a muse, but that seems highly unlikely based on the sharp choices they made.

Arc Raiders: the Unc Raider

Looking at their game, I don’t see “general shooter fans”. I see a muse who massively values their time. They probably grew up on sci-fi films with a specific 70s/80s aesthetic and prizes nostalgia. The Unc, as you’ve likely guessed by now, is probably male, likely 30-40 years old, and working a full time job. The design and art style leans heavier on Western region preferences. These Unc Raiders are PC focused and likely have a strong preference for accessing games through Steam. They’re someone who wants the high stakes of an extraction shooter but with a level of polish and “cool” that the genre often lacks. My take is that Embark clearly tried to distance from the core extraction community, and likely wanted to win with those that have never played an extraction shooter before. Looking at the responses of creators who are diehard Escape from Tarkov fans for example, many of them appear to still prefer Tarkov’s laser sharp focus on PVP and mil-sim aesthetic, and for the most part eschew Arc Raiders.

Fellowship: Former Raider Dad

With Fellowship, just looking at the website, Steam page, and their trailer, it should become clear who this game was trying to win with. The muse feels like the “Former Raider Dad”. Likely 30 - 40 years old, and a diehard PC purist. This is someone who loved the complexity of World of Warcraft raids back in the day, but doesn’t have six hours a night to prog raid every week. Even the UI helps you feel right at home. They want the boss fights, the team coordination, and the chase of sweet loot, but they want it in bite sized format. They’re happy to jump in and play solo and are looking for ways to connect with others. They’ve got the money to spend, so would rather skip the grind wherever possible.

With those examples, you could argue that a significant portion of the product team was looking in the mirror and developing the game for themselves. That’s fair. Let’s look at one example where the muse was likely very different from the core team.

Kim Kardashian - Hollywood: The Aspiring Fashionista

The developers at Glu Mobile were veterans used to building gritty shooters, like Deer Hunter. They weren’t the target. To make this work, they had to trade their own tastes for a deep understanding of celebrity social ladders. Their muse is likely an 18-25 year old, and a devotee of celebrity culture. They likely grew up on reality TV, “fit checks”, and the specific social hierarchies of the 2010s. A lot of the game is trying to replicate and play out their underlying motivations. A way for them to express their identity. The big hack here was obviously having Kim review and approve almost everything in the game, effectively acting as an IRL muse.

Why having a muse makes your life easier

Setting a muse adds significant clarity across development and publishing teams. Here’s why:

Sharper positioning: when you’re writing your game description, or thinking of the key messages to hit in your announcement trailer, you can’t be everything to everyone. You need to figure out who you want to be happiest. A muse lets you say, “This game is for this person”. It makes your hooks way more effective.

Clearer values: It defines what your game stands for. Players should be able to look at your game and be able to perceive who it’s trying to serve. If your muse cares about “fair play” above all else, you don’t even need to consider pay-to-win mechanics. If your muse is a “time poor parent” who only gets forty five minutes of peace after the house goes quiet, your core value becomes: respect for time.

Distribution foundation: You can start to intuit where this player hangs out, where they tend to congregate IRL or online. Should you focus on aggregating them all into Discord, Marvel Rivals style? Or should you focus on a niche set of creators? Or try to flood the market with short form content because your muse is a teen and you need to beat the algorithm?

Nucleus of your community: Every healthy community starts with a “hardcore” pioneering group that sets the tone and narrative for your game. Whether you like it or not, your first players become the gatekeepers. If your muse is someone who values sportsmanship and deep theorycrafting, your early Discord conversation will reflect that. Other players who join later may not always mesh with the pioneers. The product team also starts to hyper-serve this initial core, steering the product in that direction, so it’s critical that initial core is who you’re trying to serve in the long-term. It’s much easier to moderate and nurture a community that your game was supposed to serve in the first place.

Accelerated decisions: This is the big one. Making games, whether that’s creating them or publishing them, is the art of compromise. There’s never enough budget or time to do all the things you want to do. Should we raise the environment quality to gold, or add a new social feature? If your muse really values immersion, you fix the environment. The decisions start to become obvious, and teams can work with greater agility. The muse becomes the tie breaker.

The potential traps (and how to avoid them)

It’s not all sunshine and roses. If you pick the wrong muse, or use this concept in the wrong way, you could lead the project right off a cliff.

The muse must be attractive and winnable: You might have a muse who is “the ultimate MMO player”, but if they are currently 15,000 hours deep into World of Warcraft, they might not actually be willing to switch and consider your game. The Muse should also represent a meaningful audience size. If not today, at least over the coming years. There needs to be enough of them to actually pay the bills.

You need to capture more than just the muse: Most of the time, if you’ve been specific enough, your muse alone doesn’t represent an audience size that is sufficient for your game to be economically viable. That’s intentional. But in selecting your muse, you should be thinking through how they’re going to help you reach and chain lightning into a broader audience. The muse should provide the cultural street cred to “validate” your game, and pull the tourists or adjacent audiences in. They’re sorta like the “gatekeepers of what’s cool”. Win with them, and the rest follow in.

Avoid the average: If you take a hardcore PVE player and a competitive PVP player average them, you get a Muse who doesn’t exist. Real people often have contradictions; “averages” aren’t spiky enough. You start making PVEVP games that feel like a soup with too many ingredients. That was my impression when seeing Eldegarde…

Don’t pick an influencer as your muse: Unless you are literally building a game for them, their needs are going to be different. They probably care about “watchability”. Your average player just wants to have a good time. You should use influencers or creators within the context of what your muse might consume though, since you are trying to understand their broader consumption patterns.

Don’t ignore the unintended parties: Here’s a funny thing about games - sometimes you build a game for the Muse, and you end up attracting a huge audience for reasons you didn’t predict. CEO of Arrowhead Shams Jorjani talks about Helldivers 2 and their unintended pool of Call of Duty players in this podcast, which had some useful nuggets. If the team had pivoted to satisfy the “run and gun” habits of the COD crowd, that might have diluted the very friction that made the game a hit for the original, intended audience. Don’t lane-swap halfway, stick to your muse and be grateful for the stowaways.

Getting the whole team on the same page: If your marketing team thinks the Muse is a Gen Z competitive gamer, but your design team thinks the Muse is a Millennial nostalgia-seeker, decision making is going to be painful. The whole team needs to “embody” the muse and empathize with them. They need to understand their entire psyche and why they play games. Ideally, you’re hiring and filling critical taste-making roles with people who are this audience, or have significant ties to them.

Closing thoughts: hold the muse fixed

Once you’ve decided on your muse, your job is to speak the language of this audience. Go talk to people who fit this profile. Consume the content they consume, on the platforms they prefer. Run playtests specifically with this audience. Develop a persistent player pulse. Hire tastemakers who are or have strong ties to this player.

If your Muse isn’t vibing with your game, you have a problem, even if the rest of the team is having a blast.

Being laser focused means shaping the product around them. You hold the muse fixed, rather than search for a different audience once the game is halfway done. In a crowded market, being “good” for everyone is precarious. Being “perfect” for a dedicated core is how you build a community that can advocate for you and help you reach a broader audience eventually.

If this resonated, or annoyed you in a useful way, I’ll be writing more about defining your audience, positioning your game, solving for advocacy, AI trends for publishers, and games distribution more broadly.

Great article! I think that games being entertainment makes them where art meets product. If art tries not to offend, it won't have any rejectors but it won't have a point of view and that's what I think over reliance on market research leads to.